Google just announced AutoDraw, a machine learning-driven tool that renders your cack-handed artwork as crisp, editable line art in real time. Think of it as OCR for doodles.

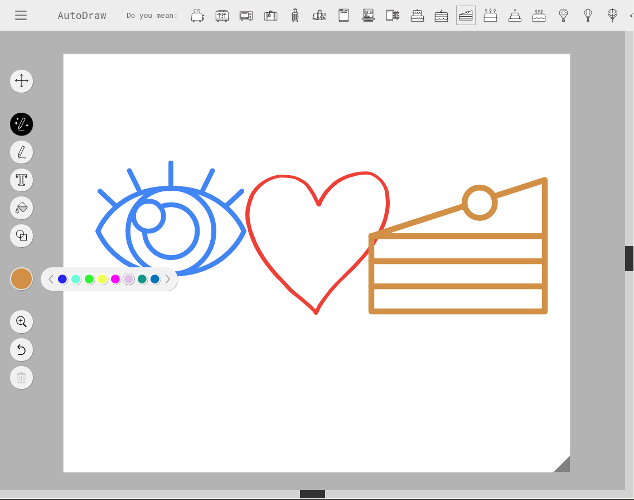

The launch trailer is a typically quirky affair, and spotlights that the tool is free, requires no download or install, and works on any device you use it on (I believe the correct term for this is ‘a website’). The trailer even has cake in it!

It’s a fantastic piece of engineering - give it a go and support it. You can even upload your own substitution image sets, which is just excellent. It’s also a great case study for the present and future of the Web.

AutoDraw is a progressive web app (PWA), part of the big G’s ongoing push to elevate the user experience and reach of the platform. It’s something I’m incredibly passionate about myself, and I’m always psyched when this sort of thing gets high visibility.

Sadly, during my first five minutes with AutoDraw I was triggered sufficiently, by something seemingly mundane and stupid, to blog about it - not as an indictment of an obviously experimental product, or as a pointless ‘native vs web’ debate, but as a measure of how user expectations, and sometimes subtle behavioural quirks, might subvert our PWA goals if we don’t take care.

Bring it back

I hit the URL on my Galaxy S7 Edge in Chrome. First impressions were great - snappy to load, with a charming laboratory/blueprint twist on Material UI. The drawing is responsive and jank-free; the centerpiece AI image recognition is a blast, handling all but my worst abominations just grand. My work was auto-saved to localStorage; transforms and fills were all intuitive… pretty magical stuff, and a great representation of modern PWAs.

After a few happy minutes playing, I popped the side menu by accident and, without thinking, tapped the phone’s Back button to reverse it. I found myself out of the site altogether, back where I was before I loaded it up.

This is one of my personal bugbears, and an unreasonably difficult thing to handle in web apps even today: the Back button as a ‘cancel’ option.

In a native app, the Back button is often a sort of UI-undo, a ‘get me out of this’ for when you’ve wandered too deep into a Facebook feed, settings menu, or whatever. If the sliding side panel on my Twitter app is open, tapping Back closes it - nothing more or less. It’s an unconscious ‘escape’ action for me, frequently to the point of spam.

In the browser, meanwhile, the Back button remains inextricably tied to the concept of navigating URL history. Under the hood in AutoDraw, opening the menu didn’t trigger a URL update, so the Back button took me back from the app itself, state be damned. (The fact there was no beforeunload alert to notify me I was leaving is another oversight.)

There are ways to make this ‘Back-as-Cancel’ behaviour happen in web apps, but they feel fairly hack-tastic, and can cause some wacky UX and browser history side-effects. A subject for another post, perhaps.

The PWA utopia

In fariness, most web apps would respond exactly the same as AutoDraw to the Back button. I normally expect and avoid this as an inevitable (and eventually/hopefully surmountable) limitation of the platform. So why pull up AutoDraw, a self-identified experiment, for it? It’s because the rest of the experience was generally so polished and immediate, I forgot I was using a browser. And here’s where things get a bit tricky for the Web platform.

The shorthand, justified or not, for progressive web apps is ‘native feel without the roadblocks’: that we can/will provide app-like experiences which are feature-rich, robust and immediate without forcing users to jump through the native app download/install/update hoops. It’s a future I am personally and professionally invested in. The coming issue, in my mind, is the blurring of the lines between native and web - not for the developer, but for the user.

I believe that the user has a well-defined, albeit somewhat subconscious, mental model of what a ‘website’ and an ‘app’ is[1], and of the perceived differences between the two. Under this model, a WordPress blog on Chrome Android isn’t necessarily going to deliver the complexity and behaviour of a Facebook or Google Maps native app. Users accept this dichotomy and have learned to live with(in) it.

Bait and switch

When a ‘website’ presents to the user the ostensible face of an ‘app’ - rich creation tools, percieved permanence, no browser UI, and design language that visually and conceptually links it to known native apps - that expectation is disrupted. The mental bar for behaviour and quality of experience is raised.

With AutoDraw, as mentioned, the app initially reflects and magnifies this expectation shift with high interactivity (like pinch-twist transform and scale!) and an explicit purpose of utility. Compounding the issue is Google’s own marketing: that this no-install, no-download, works-anywhere tool is a superior one. (No web developer I’ve teamed with would ever say out loud that a site ‘works everywhere’, but whatever.)

It’s in this elevated state, this uncanny valley between Web and native paradigms, where the most damage can be done to the user experience, their view of the product, and ultimately their perception of the platform overall. We have set the user up, often explicitly, to expect an ‘app-like’ experience, yet fail to preserve the illusion, or are prevented from doing so by the limitations and quirks of the platform. The Back button is the example I’ve focused on, but there are others in AutoDraw, and across the entire spectrum of web app experiences, that recur with impunity. Again, perhaps another article/rant in the near future.

A bleak picture

I’m not beating on AutoDraw; as I said, it’s awesome, and represents many of the very things I want the Web to be. Yet it also illustrates where the platform, and we as developers, can fall short in subtle ways. Yes, it’s an experiment, and yes, it’s free, and yes, the Back button and other niggles could be overcome with clever coding and hacks. But they weren’t.

And to be honest, they usually aren’t - all over the Web, ‘experiment’ or otherwise; it looks and works just like an app… until it doesn’t.

As a developer, I understand the circumstances and quirks around these problems (and potential solutions) fairly well. I’ve certainly never even tried to solve the Back button thing in production, or had much success in prototype. I sympathise deeply.

The average user, however, won’t ever think ‘oh it’s a web app, not native’, or anything remotely forgiving. They will just mentally file it alongside the other myriad shitty experiences they have - daily - on the mobile web, but marred yet further by the frustration of the almost good enough. Just like an app, but not quite.

And when the next high-profile PWA comes along, no matter how successful it may be, that user may weigh up their past negative experiences, and - in a climate of content-monetization desperation where the egregious likes of LinkedIn openly doorslam mobile web visitors to literally say ‘download our app, it’s way better’ - they may just decide that the PWA is not worth the hassle. And given the stakes, not to mention our pride in our work as web developers, that would be a great shame indeed.

preventDefault()

Hope you enjoyed that slice of post-Web dystopia. Hard to believe this all came from accidentally hitting Back.

As I said at the top, this is not about ‘native vs web’. I believe the two can co-exist and complement each other very well. And of course I remain a staunch believer in PWA principles such as those used by AutoDraw, and the future of Web apps in general.

If there’s one TL;DR to it all, it’s this: we can’t afford to half-ass these hybrid ‘site’/’app’ experiences, else we run the risk of ostracizing users further than if we had kept a much clearer distinction between the two forms. We need to be honest with ourselves about the feel of our web apps; test everything on devices, and early; and be prepared to get some dirty hacks on in the service of a greater user experience. Eventually, hopefully, the platform will catch up.

That, or we’ll all be writing Facebook Instant Articles full-time in a couple of years. That would be dystopian.

- NJM

[1] Users have no fucking idea what a ‘web app’ is. Don’t bother trying to convince yourself otherwise.