My self-consciously self-applied label of ‘game jammer’ was put to the test last weekend at GameCraft 2017.

I have participated in several Ludum Dares and Global Game Jams over the past few years, with varying degrees of success. Sometimes I code, do music, or both. My compositions for Dark Soils and Gradience are pieces I’m actually quite proud of, and I’ve done an awful lot of JavaScript for various games over the years. I relish a game jam as an exercise in inspiration, collaboration, and frankly not having to give too much of a shit about standards and practices for a change.

Unlike the aforementioned weekend-long events, GameCraft provides a mere 8 hours in which to deliver a game on a given theme.This year I wanted to attempt something solo: concept, code and aesthetics all in my egotistical hands.

And so I found myself in Farset Labs at 10am on a Saturday morning, and with just a laptop and grim determination on my side, set to work. The theme was ‘FAKE NEWS’, my idea was a Space Invaders-esque satire of the Trump administration’s adversarial relationship with the free press, and I was determined to succeed.

…Eight hours later, while everyone else was occupied with playing each others’ creations. I quietly made an exit. Despite working head-down for the entire duration, with barely a break to eat, I had nothing playable to show anyone.

It was a frustrating and demoralising experience, but not without lessons to learn. This post is an effort to document those lessons, and to make sure I can do better in future.

Set the groundwork in advance

The general conceit of a game jam is that everything is done on-site during the event: no upfront coding or design beforehand.

I tend to be quite strict with myself about this, often showing up with my laptop, an empty folder, and nothing else. I then inevitably lose precious time jumping through the same old hoops: set up a GitHub repo, npm install the entire internet, pull in deps for the libraries I want to use (normally Phaser and/or ThreeJS), create repo structure, blah blah… only after all this boilerplate bullshit do I actually make the game.

Clearly this is epic time-wasting. In the case of GameCraft it cost me one-eighth of the entire event. All of this should have been done, even adding the bones of a Phaser project (to the point of having a Game instance with some empty States defined), well before the jam itself.

Veterans at these things are rarely starting ‘from scratch’. Unity fans, for example (i.e. the vast majority of participants in my experience) have an entire IDE, tools, and components for everything from physics to procedural generation to controller support. As a JavaScript dev, I should be doing my best to level the playing field by gathering libs, shims and prefabs for a faster way of getting off the ground than is possible by wiring everything up manually once the jam commences.

So, instead of going in completely naked:

- Set up the project repo in advance (including your collaborator permissions, Git clients etc)

- Pre-install your deps, build tools and scripts

- Create a skeleton project with appropriate directory structure and entry point

- Ensure you have a watcher, transpilers and whatever else you need set up and working

- Collect libraries and shims to make things work more easily

As a final note on this: it may not be cool to say it, but in my experience, no-one checks or cares if you go in with some work done beforehand. It’s very much an honour system, and you get out what you put in. So don’t have a fucking full game pre-made that you just tweak to suit the theme on the day, but do have a project set up and ready to move on as soon as the event starts.

Pick the right tools (and know them)

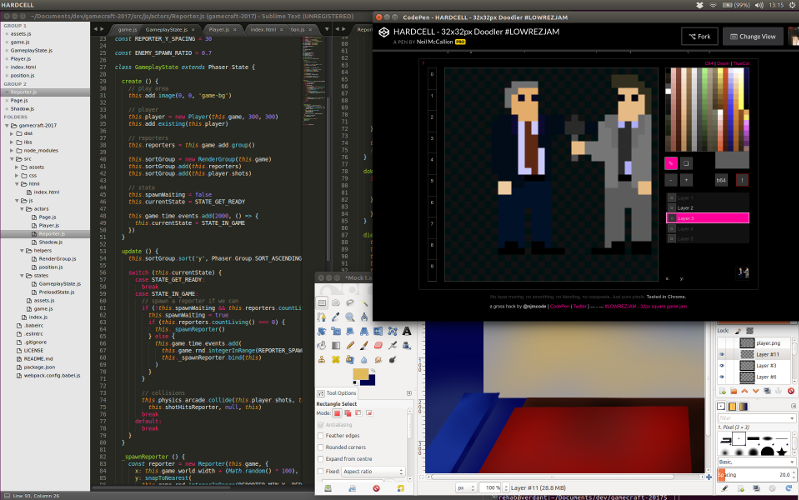

I suck at art. Basic pixel art was the best I could hope to muster at GameCraft, but unfortunately I did not take the time to practice or research editors. I ended up using HARDCELL, an experimental Canvas painter I knocked up for kicks a few years ago, and GIMP for edits and backgrounds. These were not the right tools for the job I was attempting.

HARDCELL is quick to use and a fun distraction, but is not polished or flexible enough. And GIMP is, by its own definition, not a drawing program, and lacks even the most basic vector capabilities. For art, I should have picked a good pixeller from the many out there and taken the time beforehand to play with it, and also should have got some version of PhotoShop or Illustrator running on my Ubuntu laptop.

I suffered on the coding side here too. Despite having used Phaser for at least five game jams, I am far from an expert with it, and wasted much time reading docs, working around changes, and generally fighting against the framework instead of with it. At GameCraft I also had the bright idea to do Phaser in ES6 for the first time, and the inevitable learning curve ate yet more time that I simply didn’t have. In a jam scenario, no-one gives a shit about the quality of your code, just the end result, so I should have stuck with ES5 and spent time beforehand getting (re-)acquainted with Phaser.

- Use tools that you know well and enjoy using, and that won’t get in the way of your productivity

- Get very comfortable beforehand with your art program, game framework, music DAW, text editor, programming language, etc etc…

- A jam is not time to try something new with your fundamentals (i.e. using a new language or syntax, a brand new game framework, etc)

Mechanics over aesthetics

Game jams excite my imagination. My mind runs riot with concepts and ideas. I also fancy myself a semi-decent art director (even though I suck at art!), and like to ensure a certain consistency of theme and design even in a game jam. I can’t help but create documents and write things down - a mixture of being a project lead at work and mild OCD.

And so at GameCraft I actually put time in on a mini-spec doc and mood board with on-theme visuals: Fox News graphics, election campaign banners etc. This was a great visualization tool, but led me to focus way too much on aesthetics I would have little to no hope of achieving in the timeframe.

This time should have been spent hooking up a moving red square, a bunch of moving grey squares, and making the red square shoot at the grey ones. That’s the central mechanic of my game idea. Getting that working, then adding some twists like specific targets to hit, wave spawning and scoring, should have been my primary focus, only followed afterwards by making pixel art of the White House press room and a Sean Spicer-alike physically throwing pieces of legislature to repel an ethnically-diverse mob of encroaching journalists and reporters. (Yeah.)

Get the game working first, then make it look decent. Otherwise, as I did at GameCraft, you end up with something that looks half-cool but offers nothing as a game.

- Get the fundamentals of your game (traversal, scoring, skill challenges) working ASAP

- Use primitives and placeholder art while working on the core game loop

- Don’t waste too much time on art direction and visual theming

- Only make it look good/better after it is playable

- If you have an artist, use them!

Make it simpler (yes, even simpler)

As mentioned, the ideas can flow thick and fast at game jams. The tough part is finding a core idea and polishing it, without getting bogged down in fifty ‘great ideas’ that you will never do justice to. It’s the Unix philosophy of ‘do one thing well’ - less Grand Theft Auto, more Canabalt.

What is the ‘one-liner’ for your game mechanic? Mine was (supposed to be) ‘cull the enemy journalists from the room to fill your approval meter’. Sounds very simple, but under scrutiny it betrays several hidden complexities that all eat up precious time to design and build.

‘Cull the enemy journalists’ suggests multiple NPC types, selective targetting/scoring, and the need to balance spawns and enemy ratios. A lot more complex than ‘Sean Spicer Space Invaders’ (what my one-liner should have been, really) where it’s player vs everything else on the screen, no questions asked.

‘Fill your approval meter’, meanwhile, implies an advanced scoring mechanic with win/lose states. This sort of thing can be hard to balance, and is again more complex than the Space Invaders model where you just have to clear the screen to win.

None of this is to suggest that my original idea isn’t a viable one, or that you can’t aim high and use complex and rich mechanics in your jam idea, but that the simplest version, the MVP, is what you should build first. Do it quick and well, and you have a solid playable foundation for visuals, additional mechanics etc to be added to. And if it takes longer than you expected, you’ll be grateful you kept it simple and still have a shot at delivering something.

- Pare your idea down to its very essence and build that first

- It’s never as simple as it could be

- Question yourself at every stage of the design and development process

- Things always take longer than you imagine they will

Get help

Working solo for the first time was by far the hardest part of GameCraft for me. In previous jams I’ve worked with and relied upon people I trust who also happen to be better programmers, artists and game designers than me. At GameCraft, I insisted on doing it alone, even turning down an on-site offer to collaborate. It’s important to test oneself and stretch one’s limits, but combined with the timeframe, my lack of art abilities, and my attempt at an ES6 Phaser build, flying solo was likely doomed to failure.

Many jam participants link up with strangers at the event, creating teams on the fly. Not my idea of fun - I tend to be quite assertive and jump on ideas, so I rely on people I know and trust to deliver. I should have recruited one of my usual collaborators for GameCraft, or at worst joined an existing team and tried to convince them of my ideas. Under such restrictive circumstances, we need all the help we can get.

- Work with people you trust and who complement your skillset

- Seek help and collaboration wherever it will make your life easier

- The choice between asking for help and failing to deliver is no real choice at all

CONTINUE / QUIT

A lot of this is common sense, and I make the same mistakes pretty much every time. But in the heat of the moment, when your creativity conspires to make you bite off more than you can chew; when you feel the pressure of the time limit and the weight of your own expectations bearing down on you; that’s when these lessons should be most useful.

I hope that by documenting this stuff that I will do better next time, and that others may also benefit. Game jams can be some of the most rewarding and fun creative experiences you can have. I would highly encourage anyone reading this to take part and see how you do.

The code for my abortive GameCraft entry is available on GitHub. At time of writing it’s still not in a playable state, but who knows, by the time anyone reads this, it might be further on. I haven’t come up with a title yet, but I was thinking of calling it Post-Truth Press Pounder Turbo or something equally gratuitous and preposterous. Suggestions welcome.

- NJM